'The Ten-Cent Plague' author David Hajdu at Wordsmiths Books in Decatur, Thursday, February 12

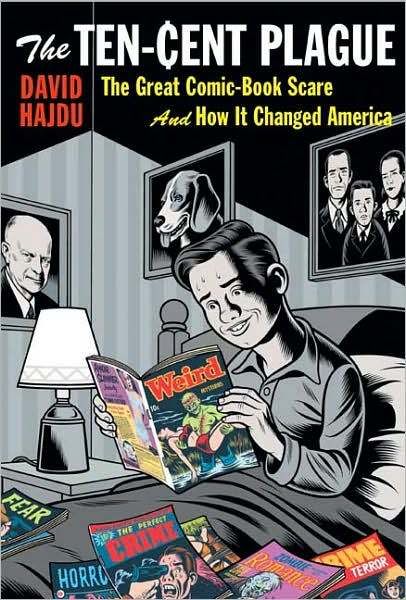

This Thursday, Cable & Tweed is co-sponsoring a visit to Decatur's Wordsmiths Books by author and Columbia University journalism professor David Hajdu. His most recent book, The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America

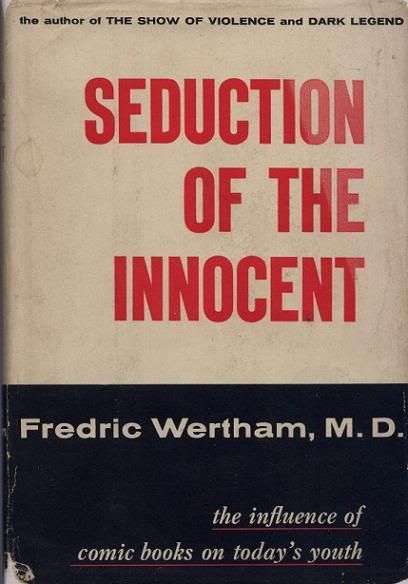

For those familiar with this episode in America's cultural history, many of the details will be well known. Although hysteria about the corrupting force of comics came and went throughout the early twentieth century, it hit a high point with the convening of congressional hearings in the early 1950s and the publication of Dr. Frederic Wertham's Seduction of the Innocent in 1954. He followed many others in arguing that comics had a detrimental effect on youth. Although Wertham's was not the only voice raised in opposition to comic books, it resonated with America's mothers and moralists like few before. While Wertham's tale is the best known to emerge from this era of comics history, Hajdu digs deeper to explore the numerous actions against comics in America as well as the concurrent growth and contraction of the industry. He did so by conducting over 150 interviews with comics veterans and uncovering more primary and secondary sources on the topic than I realized were available. It's a fascinating bit of American cultural history.

David Hajdu

-----------------------------------------------------------------

This week, Hajdu was kind enough to take time out of his busy schedule to answer questions that I sent him via e-mail.

C&T: Famed artist Al Williamson's quip that "[i]t was a bad time to be weird" (p. 210) sums up the situation examined in The Ten-Cent Plague pretty succinctly. I have to wonder, though, if there is ever a good time to be weird without provoking the powers that be. As you note, attacks on popular youth culture are cyclical and recurring. In my own formative years such attacks were made on heavy metal, rap music, "naughty" cartoons (e.g., Beavis & Butt-Head), and violent video games (among other supposedly corrupting forces). What about the attacks on the comics industry drew you to this topic a full half-century after the key events?

DH: I love that comment from Williamson. It would make a good book title – or perhaps a better song title. I’ll have to go visit Williamson again, with a guitar.

No time is exactly like any other time, of course, despite the recurrence of some themes in history. If we think of weirdness as bohemianism, that’s something that’s had a kind of cultural currency since 17th-century France. Rimbaud is forever cool, at least to young people interested in establishing their own generational identity by defying the standards of their parents. That said, each youth culture sets its own standards of weirdness, and they’re frequently rigid or parochial. When the Beatles came along, Elvis called them “weird” and “queer.” By the early ‘70s, when glam rock along, the Beatles no longer seemed so transgressive. They seemed like squares.

I was drawn to the subject of my book in large part because I didn’t understand it well. It represented a challenging new area of inquiry for me.

C&T: The aspect of The Ten-Cent Plague given the most attention is its focus on legislative responses to the perceived threat of comics as fostering juvenile delinquency. The congressional hearings of 1950-54 in particular remain captivating as both public spectacle and an example of legislative overreach. I wonder, however, about their depiction in the book. There seems to have been some balance in the 1950 hearings headed by Senator Estes Kefauver (D-TN), but nothing of the sort in later hearings. Is that a fair assessment, or were there dissenting voices in later hearings that did not make it into the book?

DH: No, I didn’t rig the evidence. I tried to convey the proportion of events as accurately as I could.

C&T: In your assessment, to what degree were elites' concerns about comics genuine rather than fueled by electoral concerns, self-promotion, or a desire to sell books and periodicals? Discerning the motivation of a Frederic Wertham, for example, hardly seems straightforward.

DH: When I started my research, I wondered if the hysteria over comics would have happened without Wertham, and I was surprised when I found that it DID happen without him -- that is to say, it began quite a while before he joined it. Wertham became important as a catalyst and as the public face of the campaign against comics. But he didn't start it; in fact, he didn't emerge as a prominent critic of comics until 1948, a full eight years after Sterling North, the children's author and book critic, wrote the newspaper column ("A National Disgrace") that was the manifesto of comics critics.

North sounded like Wertham before Wertham did. He called comics "badly drawn, badly written and badly printed -- a stain on young eyes and young nervous systems," and he describe the "effect" of comics as "that of a violent stimulant." He charged comics publishers with being "guilty of cultural slaughter of the innocents," foreshadoing the title of Wertham's book by fourteen years, while echoing the criticism of turn-of-the-century newspaper strips. That first piece of North's on comics (and it was only the first) was reprinted in forty newspapers around the country, as well as in the journal of the National Parent-Teachers Association.

A few years later, a Jesuit priest named Robert E. Southard took up the crusade against comics, making the first charge, in print in 1944, that comics were "largely responsible for juvenile delinquency." Parochial schools distributed a list of "objectionable" comics that Southard made, and they used it to organize protests against comics and public burnings as early as 1945, three years before Wertham turned his attention to comics. Wertham and the comics crusade -- or, more accurately, the multiple crusades against comics -- are not interchangeable.

C&T: In my day job I am a social scientist, and I appreciate that The Ten-Cent Plague addressed the results of empirical studies in the 1950s regarding the relationship (or lack thereof) between juvenile delinquency and comic books. I was struck, but not shocked, by the fact that none of the scholarly or peer-reviewed research identified a causal relationship between comics and crime despite claims by various politicians and moralists. Why weren't these studies more influential? Were Wertham and his ilk simply better at self-promotion and rhetoric than their counterparts?

DH: Wertham clearly had an appetite for attention, and he understood how to use the media.

There were several serious studies of comics reading and scholarly papers on the subject published in the late 1940s, and most of them came to the conclusion that comics did no particular harm to young minds. They got very little attention in the popular press.

For instance, the November 1948 edition of the Journal of Educational Research included a study of 635 elementary-school kids in Farmingdale, New York, and it found no "significant differences between those children who read comic books, attended moving pictures, and listened to radio programs to the greatest extent and those who participated in these activities seldom or not at all."

In December 1949, after the early peak of hysteria over comics in 1948, the Journal of Educational Sociology devoted an entire issue to comics, and all the papers in the journal were tempered or positive about comics. This issue included a couple of fervent defenses of comics and critiques of Wertham's methods, including "The Comics and Delinquency: Cause or Scapegoat," by Frederic M. Thrasher of NYU. As Thrasher wrote, "In conclusion, it may be said that no acceptable evidence has been produced by Wertham or anyone else for the conclusion that the reading of comic magazines has or has not a significant relation to delinquent behavior."

C&T: My own inclination is to shun censorship and reject many of the arguments made by Wertham and his allies, but I can empathize with their concerns about graphic imagery in the hands of children. It seems that some comics professionals did as well (including UGA graduate Jack Davis, incidentally). Given that, why didn't the comics industry take its own Comics Code in 1948 more seriously? Is there evidence that age restrictions were ever considered for particular comics in the spirit of the modern film and television ratings? It seems that such a system might have blunted much of the later controversy, though it might have hurt the bottom line.

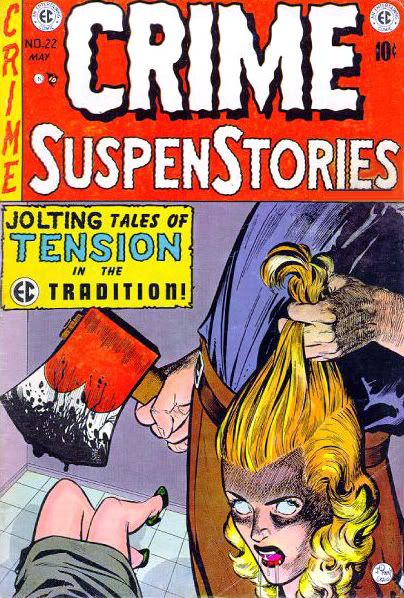

DH: Comics publishers did quite a bit to tone down their content after the early peak of the comics hysteria, in 1948, but they concentrated on crime content. The first wave of of comics regulations focused primarily on crime comics, on the grounds that the depiction of criminal acts in the panels might inspire their readers to act criminally. As a result, comics publishers shifted the tone of their crime titles or discontinued them. Only two newsstand dealers were actually arrested for selling crime comics, as far as I know; but the legislation against crime comics, in concert with the atmosphere of panic over their role in changing juvenile mores, led publishers away from crime. They turned to other genres, including horror and romance, proceeding blithely on the misconception that only crime comics could qualify as criminal.

C&T: While reading 'The Ten-Cent Plague' it would be difficult not to notice the attention given to EC Comics in its various incarnations. In fact, the book serves as a notable history of that imprint as well as broader attacks on comics. One gets the impression that EC's history is closely correlated with that of the industry as a whole, including its flame-out in the 1950s. Was it your intention from the start to focus on EC to such a degree?

DH: I gave EC the attention I gave it in part because EC comics were so serious and ambitious as art. One of the reasons I care about the debate over comics is that I care about comics. The debate over comics was a debate over not only moral values, but aesthetic values. The clampdown on comics, which resulted in the demise of EC, is tragic because it destroyed something of value.

C&T: In the course of a project of this magnitude, one inevitably learns things that are unexpected or stumbles onto wonderful artifacts. Do any such discoveries stand out in your mind? Was there a particular anecdote or fact that you wish had made the final manuscript, but did not?

DH: Oh, boy…I have literally thousands of pages of transcripts from my interviews, and I used just a tiny portion of them. Most of the material didn’t make it into the final manuscript! That was my choice, though, so I’m not complaining here. I think of writing largely as the practice of oblation.

The best story I didn’t use took place after the time period of the book. That’s why I didn’t include it. It came from Stephen Sondheim, who said that when he was first brainstorming “West Side Story” with Leonard Bernstein and Jerome Robbins, he proposed to open the play with a musical number in which the Jets would sing about comic books. Showing that the kids were comic-book readers would establish immediately that they were juvenile delinquents!

C&T: The discussion at the beginning of the Notes indicates that you interviewed more than 150 individuals associated with the comic book industry during the course of your research. In fact, the list of interview subjects is downright overwhelming. Who among them did you find most interesting or impressive? Did anyone surprise you in some significant way?

DH: I’m thinking of posting all those interview on my website, since I didn’t use literally 90% of the material, and I’m not exaggerating. Who was the most interesting? Maybe Janice Valleau. That’s why I started the book with her.

C&T: Now that you have examined jazz, Bob Dylan, and comics, what can we look forward to from you in the near future?

DH: I’m just about finished putting together a collection of my essays – pieces I’ve done on music and film and comics and some other subjects over the past ten years or so – and that will be published in the fall. It’s called “Heroes and Villains.” I’ve also been working for a few years on a biography of the jazz singer Billy Eckstine – part two of a possible trilogy on African-American jazz singers from Pittsburgh named Billy. All I need is a third.

David Hajdu appears at Wordsmiths Books in Decatur, Georgia, on February 12 at 7:30 PM. The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America

3 Comments:

Fascinating interview...and I'll definitely download this book onto my Kindle.

I never gave much thought to the comic book scare...'til today.

Great post.

12:24 AM

Thanks, Casey. It was a fun read, and I hope you enjoy it. I found it very informative and interesting, to be sure.

12:56 AM

The Sondheim anecdote is pretty good.

Thanks for bringing this book back to my attention.

1:12 PM

Post a Comment

<< Home